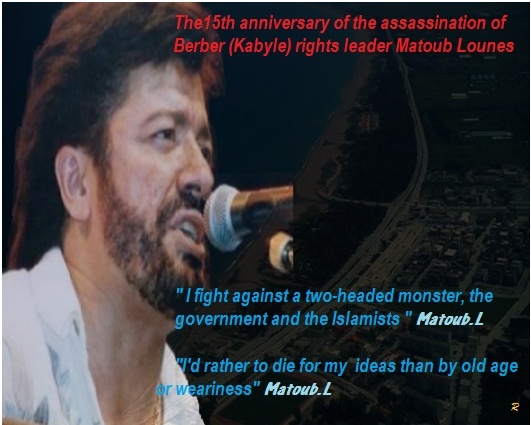

The15th anniversary of the assassination of Berber (Kabyle) rights leader Matoub Lounes

2 participants

Page 1 sur 1

K.REDA- Nombre de messages : 736

Localisation : Aokas

Date d'inscription : 31/08/2011

Re: The15th anniversary of the assassination of Berber (Kabyle) rights leader Matoub Lounes

Re: The15th anniversary of the assassination of Berber (Kabyle) rights leader Matoub Lounes

xas yeǧǧa lǧahd iɣallen-ik mazal ssut-ik ad yebbeεzeq

insoumise- Nombre de messages : 1288

Date d'inscription : 28/02/2009

A Slain Berber Singer's Voice Rouses His Hometown

A Slain Berber Singer's Voice Rouses His Hometown

A Slain Berber Singer's Voice Rouses His Hometown

By MICHAEL SLACKMAN

TIZI OUZOU, Algeria - High in the jagged mountains covered with olive and fig trees, his voice booms from a minivan as it twists along narrow winding roads to drop off students after a day of school.

Head down into this city and there he is again, this time larger than life, in a poster mounted on a cafe wall while, of course, his voice booms from the stereo behind the counter. In shops, offices, restaurants - everywhere in this region, it seems - is the voice of Lounès Matoub.

"Never surrender, never surrender," he sings, strong and folksy. "Of course times change, but you should never forget."

Someone tried to silence Mr. Matoub on June 25, 1998; his car was sprayed with 79 bullets. Instead, he became in death a powerful symbol of defiance for an ethnic minority that has challenged the government's decision to define Algeria as an Arab nation.

This is Kabylia, one of Algeria's most restive regions - home to a stubborn and proud ethnic minority of Berbers who since independence four decades ago have fought to preserve their cultural identity and independence. While politicians and village elders have helped lead the fight, the soul of this struggle is captured in music, especially the music of Mr. Matoub.

"Music is much more a symbol of our identity than it is about entertainment," said Ousmail Abderrahmane, owner of a music shop in this city, the Kabylia region's capital.

Considered by many the original inhabitants of northern Africa, the Berbers had their own language, music and culture until the region was effectively Arabized as Islam spread a thousand years ago.

While many people in Algeria have Berber ancestors, those in the Kabylia region cling to their language and customs, even while adopting Islam as a faith. The women wear bright-colored traditional dress, and the men participate in elder councils, which govern affairs in their mountain villages. The Berbers were also known as fierce fighters, and Kabylia contributed many forces during the eight-year war of independence from France.

But after more than a century under French rule, Algeria's new government decided to forge an Arab identity, and the Berbers felt betrayed. They had believed that independence would give them greater autonomy over their affairs, not less. Over time, the Berbers of Kabylia began to organize, politically and socially, staging boycotts and acts of civil disobedience to force the government into talks. There have been violent confrontations as well.

In battles of identity, language often becomes the front line, and so while the issues for the Berbers are many, the flash point is the government's insistence that Arabic serve as the only official language. People from this region want their language, Tamazight, to have equal status, but the president refuses to budge.

"Algeria above all," read a recent headline in El Moudjahid, the government-controlled daily newspaper. "The head of state has chaired a rally on Thursday in Constantine, and he has stated Arabic will remain the sole official language."

Through brutal force and careful political calculation, the government has managed to secure the country. But the people of Kabylia are still fighting: boycotting elections, refusing to pay utility bills, insisting on greater democracy and some degree of self-rule. Music has helped pass the struggle from generation to generation, to unite political factions behind common ideas and to help keep the fires of resistance burning.

The region's four most popular musicians sing about the struggle for identity. Indeed, one of them, Idir, has an album titled "Identity." But Mr. Matoub remains the biggest seller, said Mr. Abderrahmane, the music shop owner. His lyrics tell of daily life in Kabylia, of oppression and of contemporary events, like the day in 2001 when the military opened fire on citizens protesting and rioting after a local boy was killed while in custody.

"O my life, o my life, the mountains are my life, Kabylia is my whole life." The words are Mr. Matoub's, but they are being sung softly by three young women standing side by side on the edge of a mountain road. Dahbir Ouidir is 19 years old. Sabina Wahan and Yasmine Lasmi are 16. They are a year behind in their studies because they joined thousands of other young people in a one-year school boycott as a sign of defiance.

They came home from school in a minivan, as the driver played a Matoub album. Stepping out, they said they would be happy to sing their favorite Matoub song, and soon the three , eyes closed, drew a crowd.

"People identify with his poetry," Ms. Ouidir said, her face flushed after singing.

Samir Rehane, a tall, slender 18-year-old with a book bag under his arm, overheard the conversation and walked over. "Matoub is a son of my village," he said. "He is a teacher for us. He is a symbol of freedom."

Down the road, in the village of Taourirt Moussa, a red marble tomb is decorated with dozens of tiny Algerian flags. It is where Mr. Matoub is buried, and it has become a pilgrimage site. The tomb is in front of Mr. Matoub's childhood home, which has been transformed into a shrine. The bullet-riddled Mercedes sedan he was driving when he was killed is parked in the garage, with a piece of tape on the driver's seat that marks a hole from the fatal bullet.

"We are not only interested in his music," said Ali Yashir, 21, who visited the grave one recent day. "We are interested in what he stands for. His struggle and his ideas will go on forever."

There is another shrine for Mr. Matoub at the mountainside scene of the ambush. A large metal sculpture, it depicts the Berber symbol of freedom, a crude stick figure of a person with raised hands. Mounted between the hands is a drawing by a popular Algerian political cartoonist, Ali Dilem, which was used as one of Mr. Matoub's album covers.

There is also a carved stone plaque nearby with a phrase that might well have been a chorus in one of Mr. Matoub's own songs: "Even if you are dead, you are still alive. A History. A Struggle. A Hope."

New York times

By MICHAEL SLACKMAN

TIZI OUZOU, Algeria - High in the jagged mountains covered with olive and fig trees, his voice booms from a minivan as it twists along narrow winding roads to drop off students after a day of school.

Head down into this city and there he is again, this time larger than life, in a poster mounted on a cafe wall while, of course, his voice booms from the stereo behind the counter. In shops, offices, restaurants - everywhere in this region, it seems - is the voice of Lounès Matoub.

"Never surrender, never surrender," he sings, strong and folksy. "Of course times change, but you should never forget."

Someone tried to silence Mr. Matoub on June 25, 1998; his car was sprayed with 79 bullets. Instead, he became in death a powerful symbol of defiance for an ethnic minority that has challenged the government's decision to define Algeria as an Arab nation.

This is Kabylia, one of Algeria's most restive regions - home to a stubborn and proud ethnic minority of Berbers who since independence four decades ago have fought to preserve their cultural identity and independence. While politicians and village elders have helped lead the fight, the soul of this struggle is captured in music, especially the music of Mr. Matoub.

"Music is much more a symbol of our identity than it is about entertainment," said Ousmail Abderrahmane, owner of a music shop in this city, the Kabylia region's capital.

Considered by many the original inhabitants of northern Africa, the Berbers had their own language, music and culture until the region was effectively Arabized as Islam spread a thousand years ago.

While many people in Algeria have Berber ancestors, those in the Kabylia region cling to their language and customs, even while adopting Islam as a faith. The women wear bright-colored traditional dress, and the men participate in elder councils, which govern affairs in their mountain villages. The Berbers were also known as fierce fighters, and Kabylia contributed many forces during the eight-year war of independence from France.

But after more than a century under French rule, Algeria's new government decided to forge an Arab identity, and the Berbers felt betrayed. They had believed that independence would give them greater autonomy over their affairs, not less. Over time, the Berbers of Kabylia began to organize, politically and socially, staging boycotts and acts of civil disobedience to force the government into talks. There have been violent confrontations as well.

In battles of identity, language often becomes the front line, and so while the issues for the Berbers are many, the flash point is the government's insistence that Arabic serve as the only official language. People from this region want their language, Tamazight, to have equal status, but the president refuses to budge.

"Algeria above all," read a recent headline in El Moudjahid, the government-controlled daily newspaper. "The head of state has chaired a rally on Thursday in Constantine, and he has stated Arabic will remain the sole official language."

Through brutal force and careful political calculation, the government has managed to secure the country. But the people of Kabylia are still fighting: boycotting elections, refusing to pay utility bills, insisting on greater democracy and some degree of self-rule. Music has helped pass the struggle from generation to generation, to unite political factions behind common ideas and to help keep the fires of resistance burning.

The region's four most popular musicians sing about the struggle for identity. Indeed, one of them, Idir, has an album titled "Identity." But Mr. Matoub remains the biggest seller, said Mr. Abderrahmane, the music shop owner. His lyrics tell of daily life in Kabylia, of oppression and of contemporary events, like the day in 2001 when the military opened fire on citizens protesting and rioting after a local boy was killed while in custody.

"O my life, o my life, the mountains are my life, Kabylia is my whole life." The words are Mr. Matoub's, but they are being sung softly by three young women standing side by side on the edge of a mountain road. Dahbir Ouidir is 19 years old. Sabina Wahan and Yasmine Lasmi are 16. They are a year behind in their studies because they joined thousands of other young people in a one-year school boycott as a sign of defiance.

They came home from school in a minivan, as the driver played a Matoub album. Stepping out, they said they would be happy to sing their favorite Matoub song, and soon the three , eyes closed, drew a crowd.

"People identify with his poetry," Ms. Ouidir said, her face flushed after singing.

Samir Rehane, a tall, slender 18-year-old with a book bag under his arm, overheard the conversation and walked over. "Matoub is a son of my village," he said. "He is a teacher for us. He is a symbol of freedom."

Down the road, in the village of Taourirt Moussa, a red marble tomb is decorated with dozens of tiny Algerian flags. It is where Mr. Matoub is buried, and it has become a pilgrimage site. The tomb is in front of Mr. Matoub's childhood home, which has been transformed into a shrine. The bullet-riddled Mercedes sedan he was driving when he was killed is parked in the garage, with a piece of tape on the driver's seat that marks a hole from the fatal bullet.

"We are not only interested in his music," said Ali Yashir, 21, who visited the grave one recent day. "We are interested in what he stands for. His struggle and his ideas will go on forever."

There is another shrine for Mr. Matoub at the mountainside scene of the ambush. A large metal sculpture, it depicts the Berber symbol of freedom, a crude stick figure of a person with raised hands. Mounted between the hands is a drawing by a popular Algerian political cartoonist, Ali Dilem, which was used as one of Mr. Matoub's album covers.

There is also a carved stone plaque nearby with a phrase that might well have been a chorus in one of Mr. Matoub's own songs: "Even if you are dead, you are still alive. A History. A Struggle. A Hope."

New York times

K.REDA- Nombre de messages : 736

Localisation : Aokas

Date d'inscription : 31/08/2011

Sujets similaires

Sujets similaires» TIZI N BERBER: LE MAK ORGANISE UNE CONFÉRENCE-DÉBAT À TAZRORT LE 27 NOVEMBRE À 15H

» Nna Aljia, la mère de Lounes Matoub avec le drapeau kabyle.

» Matoub Lounès: 10 rues portent le nom du Rebelle kabyle...en France !

» Requiem pour Matoub Lounès, le 30 juin 2012 à Montréal --- Matoub Lounès entre au Conservatoire de musique et d’art dramatique de Montréal

» ASALI N WANAY AQBAYLI DEG AT BUƐISI - Ait Bouaissi (Tizi n Berber) : Lever du drapeau kabyle le 16 juillet à 17h

» Nna Aljia, la mère de Lounes Matoub avec le drapeau kabyle.

» Matoub Lounès: 10 rues portent le nom du Rebelle kabyle...en France !

» Requiem pour Matoub Lounès, le 30 juin 2012 à Montréal --- Matoub Lounès entre au Conservatoire de musique et d’art dramatique de Montréal

» ASALI N WANAY AQBAYLI DEG AT BUƐISI - Ait Bouaissi (Tizi n Berber) : Lever du drapeau kabyle le 16 juillet à 17h

Page 1 sur 1

Permission de ce forum:

Vous ne pouvez pas répondre aux sujets dans ce forum